GCC Talks To Writer Philip Hoare

Philip Hoare is a writer, artist, film maker and curator. He is the author of nine non-fiction books including Leviathan or, the Whale, which won the 2009 Samuel Johnson prize. He wrote and presented the BBC Arena film The Hunt for Moby-Dick and directed three short films for BBC’s Whale Night. He is co-curator of the Moby-Dick and Ancient Mariner ‘Big Reads’, and is professor of creative writing at the University of Southampton. His latest book, Albert & the Whale, in which he sets out to discover why Dürer’s work endures, was recently published to great acclaim by Fourth Estate.

GCC: We are all deeply concerned about the climate crisis, but can you pinpoint a moment when thinking about your environmental footprint changed gear, and went from important to urgent; passive to active?

Philip Hoare: I think when I was travelling, in the 90s, and I realised that wherever in the world I went, there was a smudgy line on the horizon. That everything was subsumed in it. There's nothing new in that, I guess. It's why Turner was able to paint great sunsets. He didn't have to imagine them. The Anthropocene did it for him. Satan's greatest work of art, as Stockhausen said of 9/11. Then I started to see whales in the wild - in that year, ironically. For the first time since I saw a captive orca in Windsor Safari Park as a child, I was being invited to witness the culture of a species other than myself. The knowledge of how wide that gap between us is - and how we have abused that ignorance - really drew me on in my work since the beginning of this century.

GCC: What has been the most significant change you've made?

PH: Nothing I have done, or not done, has made any appreciable difference. But trying to fly less may be the least unimportant. Even though its use has enabled me to do what I do.

GCC: Do you think artists have a responsibility to engage with the climate crisis?

PH: Yes, personally. In their art? I'm not so sure. When myself and artist Angela Cockayne curated the Ancient Mariner Big Read, a digital project which involved many contributions from contemporary artists, we had a three-year-long and very passionate debate about how far we should choose work that reflected these concerns. I felt Coleridge's poem spoke so powerfully for itself that I didn't feel the art we selected should seem didactic or hectoring. That we should draw the listener/viewer in subtly. Angela wasn't so sure. Neither am I, now.

GCC: One of the major concerns within the climate change conversation is the fact that its fallout is unequally distributed across the planet. As an artist and writer, how do you approach the fact of climate injustice and the intersection between the ecological, class, race, gender and representation?

PH: Injustice knows no bounds. Just as we must equate animal cruelty with the cruelty shown to humans, we feel the imbalance and paradox invested in every action we take. But I never think about that when writing.

GCC: We asked to choose an image that is particularly meaningful to you when thinking about the environment. What have you chosen and why have you chosen it?

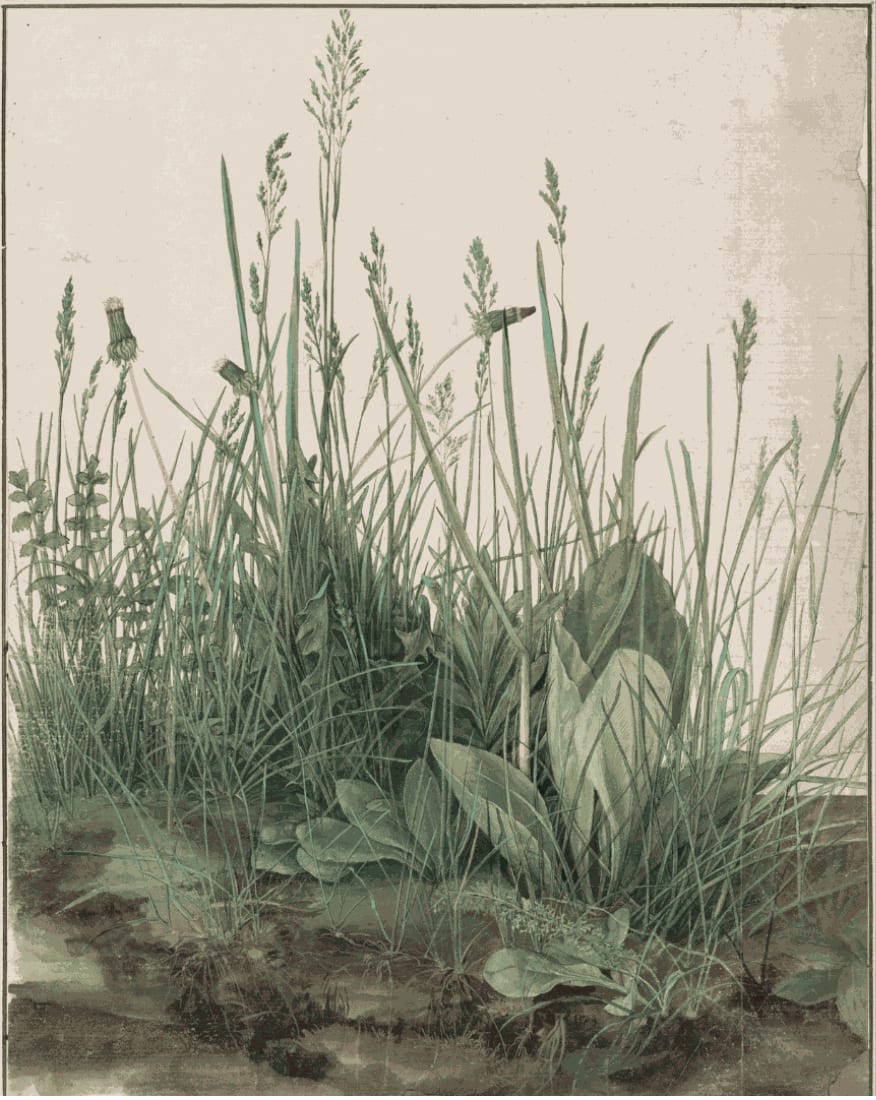

PH: Dürer's Large Turf. I imagine the artist trudging out of the city gates of Nuremberg, with a spade over his shoulder - or perhaps he had someone to do it for him. To select a random sod of turf, hoick it back to the studio, and draw it.

That very act of selection and isolation seems so incredibly modern, and so transcendent. The dandelions are about to turn into clocks. The grasses are caught on a warm, unseen breeze. The roots of the plants are visible, wriggling down into the spring-soft earth. No one drew dirt before Dürer. They didn't dare. Nuremberg was an industrial town, an augury of the age to come. Dürer's drawing - so tightly packed - is a microcosmic of a macrocosmic time and space. All the networks and resources were already in place. His turf - frail, diverse, alive - stood entirely outside all of that.

Except that it was drawn by a human hand, using industrially sourced pigments, and is now presented to you, as you and I look at it, as a digital image even now using up resources to allow it to be seen. Peel it away and there's the darkness behind, the blank blackness of what lies behind your screen.

And yet, of course, left on your retina is another afterimage, of the absolute beauty that a human mind can create.